Biographica

Sydney Chamber Opera / Ensemble OffSpring

Carriageworks, 7 January 2017

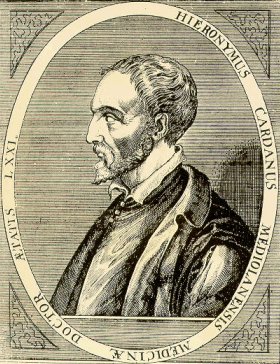

The life of scholar Gerolamo Cardano (1501-1576) is an impossible tale. Obsession. Delusion. Murder. Betrayal. Invention. No one medium could do hope to do justice to the complexity of this Renaissance (in every sense, including temporal) man, so thank goodness for opera, thank goodness for composer Mary Finsterer and thank goodness for the many hands which came together to make this palimpsest of sights, sounds, words and music.

The life of scholar Gerolamo Cardano (1501-1576) is an impossible tale. Obsession. Delusion. Murder. Betrayal. Invention. No one medium could do hope to do justice to the complexity of this Renaissance (in every sense, including temporal) man, so thank goodness for opera, thank goodness for composer Mary Finsterer and thank goodness for the many hands which came together to make this palimpsest of sights, sounds, words and music.

Gerolamo Cardano may be a fascinating forgotten genius but, be warned, he is not a nice man and he does not live in a nice world. The sixteenth century is portrayed as a series of suppurating pustules and ragged wounds against which the nascent discipline of medicine can but flail. Yes, there are a couple of violent deaths, and an ear lopping or two, but you are just as likely to be carried off by a tribe of microbes which, for Cardano, make up the intricate web of life on earth as the stars make the skies. His attempts to cure patients are haphazard, by modern standards, but his passionate desire to make sense of the universe is the saving grace of this deeply flawed character.

Finsterer, along with librettist Tom Wright, creates his life story as an episodic work,  flitting backwards and forwards in time, like a series of Holbein portraits, each coherent as a whole but studded with secrets. The non-linear narrative is confusing, even frustrating at times – meaning in spades, if you care to reflect and connect, but with a seductively fast-moving surface. There is a grief-stricken mother – Jane Sheldon, wracked with the pains of motherhood — and a child’s eye view of the universe, magically captured by Jessica O’Donoghue. There is an intricate mechanism to decipher, and multiple death scenes. And running through all of it, there is Finsterer’s delicately patterned music, repeating, evolving. I wanted to step back to take in the whole picture but, at the same time, I didn’t want to miss any of the detail.

flitting backwards and forwards in time, like a series of Holbein portraits, each coherent as a whole but studded with secrets. The non-linear narrative is confusing, even frustrating at times – meaning in spades, if you care to reflect and connect, but with a seductively fast-moving surface. There is a grief-stricken mother – Jane Sheldon, wracked with the pains of motherhood — and a child’s eye view of the universe, magically captured by Jessica O’Donoghue. There is an intricate mechanism to decipher, and multiple death scenes. And running through all of it, there is Finsterer’s delicately patterned music, repeating, evolving. I wanted to step back to take in the whole picture but, at the same time, I didn’t want to miss any of the detail.

Central to the work is the relationship between choral writing and the spoken monologue. Cardano is a speaking role — played with brilliant charisma by Mitchell Butel — while the chorus, playing multiple characters, sing and play percussion. There is scarcely any dialogue (and I wonder if it could be done with no dialogue at all to underline the different states). As it is, the combination of biographical evidence and vocal scoring makes Cardano increasingly isolated, a lone voice against a crowd which, by the power of music, can make voices heard individually and collectively.

The stage and music direction, by Janice Muller and Jack Symonds respectively, makes a tricky space work far better than should be possible. The balance between chorus, ensemble and speaking voice is cleverly done by a combination of amplification, stage positioning and orchestration — Finsterer is good at picking lines out of the morass of sound using an unusual timbre here or a high register there. And Muller explores the space fully, using a distant stage, movable screens and furniture and, as Cardano and his young daughter contemplate the universe, one of the most dramatically effective uses of projection (which has been used and abused on the opera stage in recent years) I have seen.

Mitchell Butel is a mesmerising Cardano. The way he makes the audience part of the action, part of the bemused world he is trying to enlighten, is deliciously seductive. The vocal performances are consistently good, if not yet great, and the ensemble, at least on the first night, was exciting, but still coming together. And this is one of the reasons why this work needs many more performances — it’s demanding for all involved, including the audience, but with great rewards for those who listen. I’d be happy to see any one of the twelve scenes being performed in isolation, in concert performance, and encourage new music ensembles to check it out. The final scene, in particular, is an irresistible funereal dance, driven by drums and a ground base, and spiked with chaos.

Biographica is presented by Sydney Chamber Opera in association with Ensemble Offspring as part of Sydney Festival. It plays for another six performances, until 13 January. (And while it shouldn’t be noteworthy, it’s worth noting that Biographica is the first work for Ensemble Offspring’s 2017 program, a year dedicated entirely to music by women.

It’s also worth noting that this is my first review for 2017, the first of many I hope. Reviewing is a labour of love for me, and although I’d like to think all you need is love, my writing is also improved by chocolate, coffee and your support. If you feel moved to help please take a look at my book project, http://www.unbound.com/books/sanctuary, and pledge lots of money. (I accept chocolate but at this time of year it melts).